Originally published Jan. 27, 2020, by Belleville News-Democrat

GRANITE CITY — An 83-year-old man was in the hospital with lung cancer when he learned he could be kicked out of his apartment.

It was early 2017, a few days after Laurence Madden’s 19-year-old grandson was arrested for disorderly conduct at Madden’s Granite City apartment. He received a letter from the police officer who enforces the crime-free housing policy, the city’s rules for renters.

The message said the apartment complex’s owner had to evict Madden over his grandson’s criminal charge or else the city could revoke the business license the owner needed to rent out apartments in the future.

About a month later, the charge against Madden’s grandson was dismissed. But the eviction case against Madden continued.

Like Madden, nearly half of the more than 500 people who faced eviction under Granite City’s crime-free housing rules over a five-year period weren’t accused of a crime, a Belleville News-Democrat investigation found.

The allegations were instead lodged against their family, roommates or a guest visiting them. They were left trying to convince the city or a judge to let them stay — or leaving before they got an eviction on their record, which could make landlords hesitant to sign a lease with them in the future.

In its investigation, the BND analyzed five years’ worth of documents related to Granite City’s enforcement of crime-free housing, from 2014 to 2018, using public records requests and Madison County court records.

The investigation found:

- Nearly half of the tenants who were forced out of their homes — 239 out of 510 or 46.8% — weren’t accused of wrongdoing.

- A quarter of the people who Granite City said violated its crime-free housing rules — 111 out of 433 or 25.6% — were accused of offenses that didn’t happen at the home of the renters facing eviction for it.

- In 22 households, with 36 tenants who faced eviction, the offense was calling 911 to help someone in the home who was overdosing on drugs.

- Another 35 tenants faced eviction because they had drug paraphernalia or an amount of marijuana that is now legal to buy and use in Illinois.

- Of the people who were charged with a crime, whose outcome could be determined, 59.6% were eventually convicted. The other 40.4% either had their charges dismissed in court or a judge decided to give them supervision or probation instead of a criminal record. That doesn’t include 39 people whose criminal cases are either ongoing, were tried in juvenile court where records aren’t public, were closed because the person died or is a fugitive, were simply probation violations, or could not be located in court records.

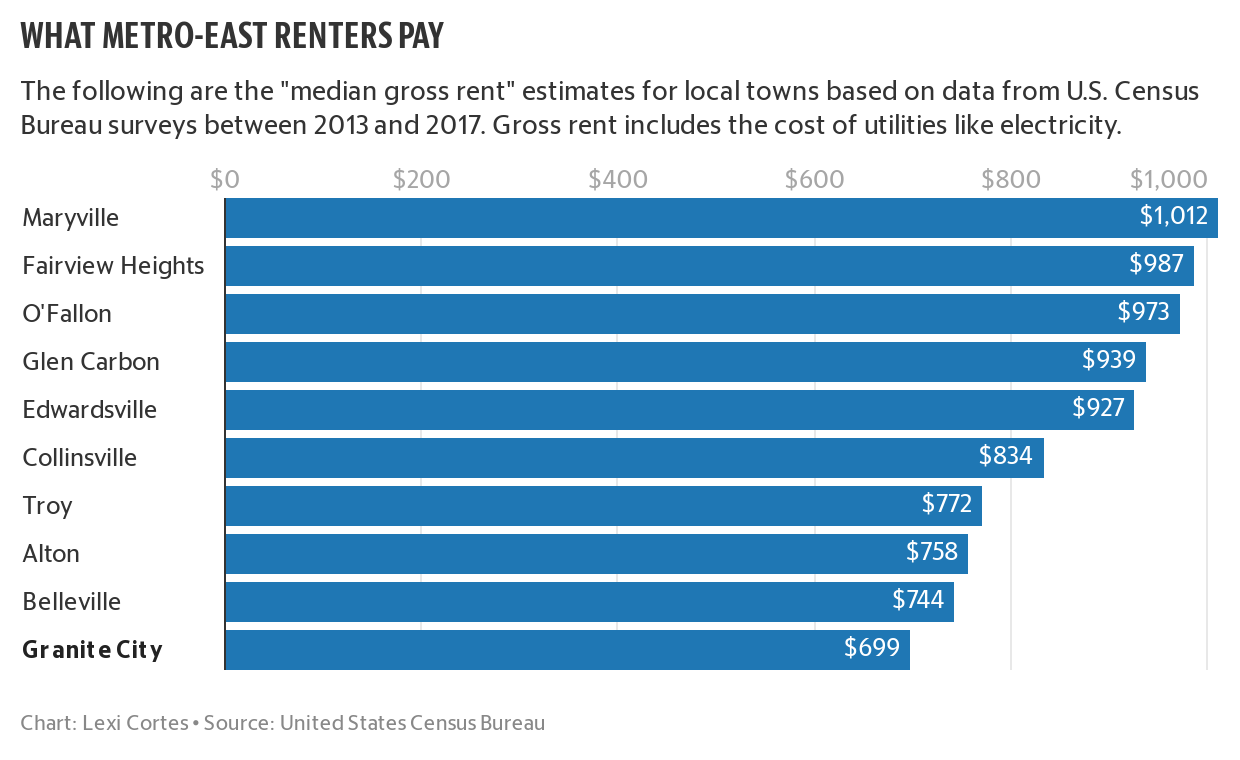

Granite City officials say their crime-free housing policy makes the community safer. Others say rules for renters across Illinois unfairly affect the poor. In Granite City, the median household income for renters is $22,060 to $42,500, far less than the typical homeowner, according to the latest estimates from the American Community Survey.

“It’s disheartening that the city is pushing low-income people into homelessness,” said Sam Gedge, a lawyer for two families suing the city over its policy.

Other metro-east cities, including Belleville, O’Fallon and Collinsville, also have crime-free housing rules.

But Granite City’s rules went further than those towns for years, calling for evictions even if the offense happened somewhere other than an apartment or rental home. Officials recently changed that part of their rules.

Granite City has been under scrutiny since August because of ongoing civil rights lawsuits that raise questions about the fairness of its policy.

Lawyers for Granite City advised city officials not to comment because of the ongoing litigation, according to Mayor Ed Hagnauer’s office. They declined to be interviewed, and police department staff didn’t respond to a request for comment. But Granite City Police Lt. Mike Parkinson, who is in charge of the program today, described it as beneficial to the community in a 2019 news release from State Sen. Rachelle Aud Crowe, D-Glen Carbon.

Crime-free housing harms people in poverty, advocates say

Jessica Barron, Kenny Wylie and their three children filed a lawsuit against Granite City in August after they learned they could be evicted from the house they are working to purchase from their landlord, who is also a plaintiff in their complaint. A second family, Andy Simpson, Debi Brumit and her two grandchildren, filed their lawsuit in October.

The families are represented by the Institute for Justice, a nonprofit that takes on cases dealing with civil liberties.

The lawsuits allege that it’s illegal to force landlords to kick people out for crimes committed outside of their homes by a guest without their knowledge, which homeowners don’t have to worry about.

Video: Granite City ‘overstepping’ in ‘crime-free’ housing enforcement, renter says

The city has said in response that tenants are responsible for anyone they allow in their homes. Granite City’s attorney Erin Phillips recently filed motions to dismiss the lawsuits because she says the plaintiffs can’t be kicked out under the new rules for renters since neither of the crimes that triggered their evictions happened at their homes.

The Institute for Justice is still fighting the rules in federal court because, even after the revision, a renter who hasn’t committed a crime can be evicted, according to Gedge, the lead attorney for the families.

If the judge rules in the plaintiffs’ favor, it could bring changes for future renters.

Gedge described the tenants affected by the crime-free housing policy as “desperately poor people.” Both Gedge and Emily Werth, an ACLU of Illinois staff attorney, said they think cities are criminalizing poverty with their rules.

Several Granite City renters whose landlords filed eviction complaints against them because of a crime-free housing violation asked for a court fee waiver and defended themselves rather than hiring an attorney because they couldn’t afford those costs. They said they were living on food stamps, unemployment or disability assistance, court records show.

Apartments and rental homes in Granite City are among the most affordable in the metro-east, according to U.S. Census data.

In their desperation to keep their home, a mother and father moved their 13-year-old son in with a relative after getting their letter from police in 2014. The boy was charged with a crime against a child on the school bus. When they didn’t show up for their court date, there was a default judgment to evict them.

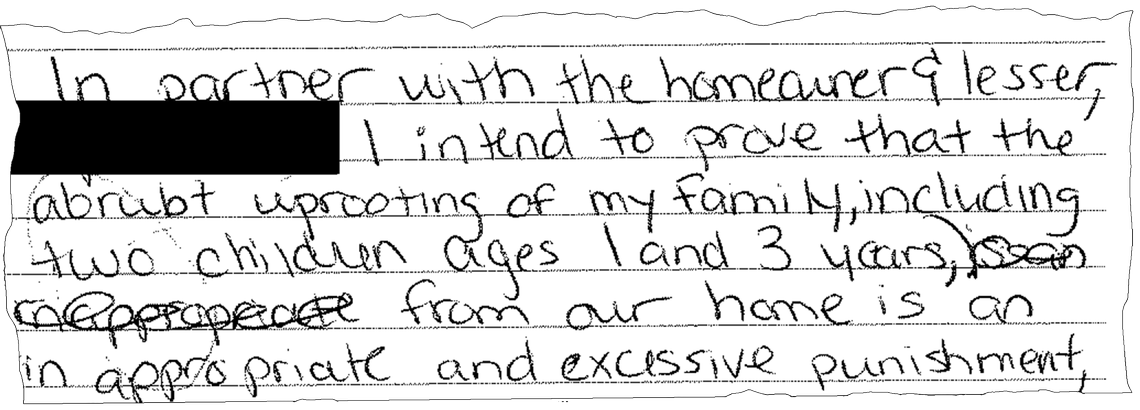

Another parent offered to move out after an unsuccessful appeal so her two children, who were 1 and 3 years old, and their father could stay. A fight in a bar had resulted in a criminal charge for her and an eviction for their family in 2015.

“As the ordinance could stand for some clarification and updating I accept my defeat,” she wrote in a letter to the city. “… I now volunteer to remove myself from the home and my roomate (sic), who was absolutely innocent may remain a tenant and continue the normal life of him and his kids.”

Many crime-free housing policies, including Granite City’s, also state that someone can be evicted for city ordinance violations, like an unkempt lawn, if they have a certain number of citations.

“Your ability to comply with the ordinance may depend on financial resources, ability or disability,” the ACLU’s Werth said, which means they could lose their home if they “don’t have the physical ability to maintain their property or the financial resources to pay someone to do it.”

Between 2014 and 2018, at least 11 renters have faced eviction over Granite City ordinance violations alone, mostly because of junk or trash on the properties. A few of them had stopped paying for their trash to be picked up, police noted in letters to their landlords.

Before she started working for the ACLU of Illinois, Werth studied crime-free housing ordinances across Illinois for the Shriver Center on Poverty Law in Chicago. In a 2013 report on her research, she advised cities not to pass the ordinances.

Why is private housing in Granite City subject to the rules?

Granite City leaders started applying rules for people who live in private rental properties in 2006 as a crime deterrent, according to the city’s responses to the litigation in court.

After seven years of enforcing evictions over allegations of crime at rental properties in town, Granite City expanded the rules in 2013 to include crimes alleged to have been committed anywhere in the city. Alton adopted similarly strict rules last year.

Granite City officials relaxed the rules in December so that renters can only be evicted for off-premises crimes if there is a conviction, citing a new amendment in the Illinois Human Rights Act as their motivation.

State law now says landlords who deny someone housing based on an arrest without a conviction are violating the tenant’s rights. But the law includes an exception: Landlords can use arrest records to make decisions about their tenants when there is “unlawful activity” on their property.

In Granite City today, an entire household can be evicted if anyone — from a child to a roommate or a guest — is accused of a crime at their rental property. A conviction isn’t required.

At a recent meeting of Granite City’s landlord association, some property owners expressed frustration with the rules, saying the city didn’t ask for their input before adding government oversight to their business. They said evictions are expensive, with court costs on top of the licensing fees they face, and that they lose revenue on their properties when tenants are forced out.

“They tell me I have to evict somebody, and they say, ‘Oh, and by the way, you get to pay for it, too.’ They’re about a grand now,” said landlord Scott Green.

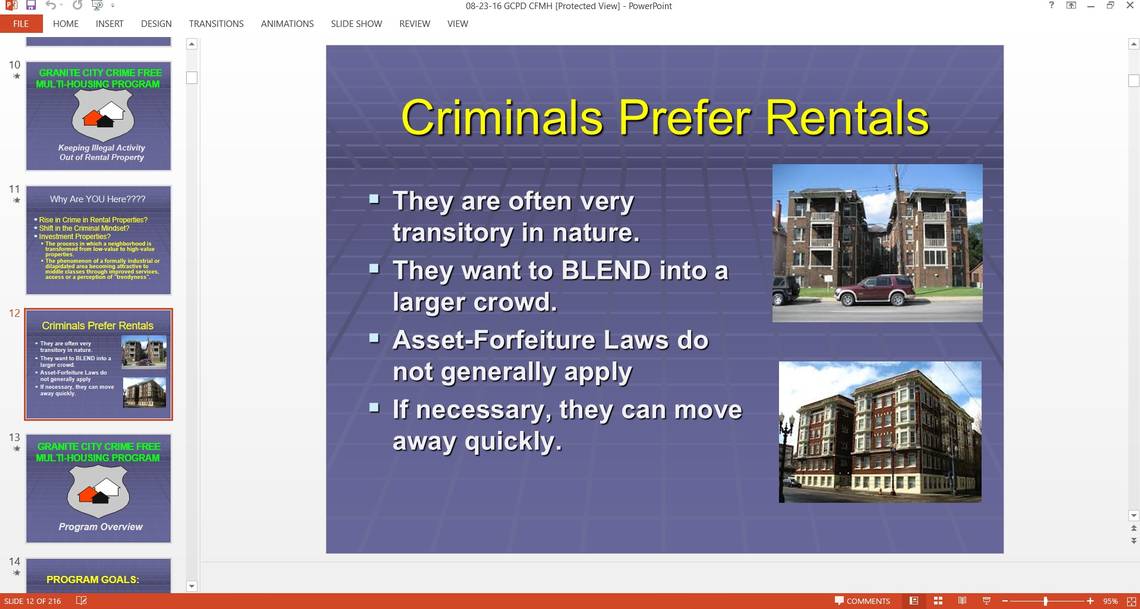

The crime-free rules also say Granite City landlords have to go through training that encourages screening potential tenants for past criminal convictions, which police say is the best way to predict future criminal activity. “Criminals prefer rentals,” the police department teaches landlords, according to a presentation on the city’s website.

‘A lot of assumptions of people with criminal records’

The rules make landlords and tenants more selective about who they allow to live in or visit Granite City’s rental properties, the city says.

“By preventing would-be criminals from having access to a home base in Granite City, the likelihood that a person will commit their criminal activity in Granite City is reduced,” it explained in court filings.

Malissa Gray, who has been a landlord in Granite City for 20 years, said in an interview that she supports the city’s rules and sets her own high expectations for her tenants because they don’t own the home they’re living in; she does. She likes the increased communication between police and landlords that Granite City’s policy created. She likes to know what’s happening at her properties.

“I just expect more. When you buy your own house, you can make your own rules,” Gray said.

Vickie Navarrete, another longtime landlord, acknowledges the rental housing industry is “not forgiving.” Property owners are responsible for the safety of everyone in the community, she said, not just the person living in their rental. Navarrete had been a landlord for 28 years and in multiple states, all with crime-free housing policies, before she retired recently. Now, she’s a property manager in Granite City.

“As a landlord, you should make sure you’re being a good neighbor to the people around you,” Navarrete said.

One of the groups that supported the Illinois Human Rights Act’s recent change, Chicago-based Heartland Alliance, eventually wants the law to include protections for people with criminal convictions, too, according to Quintin Williams, a campaign manager for the organization.

Williams said he has two felony convictions himself. He thinks it’s “unfortunate” that landlords could decide not to sign a lease with him based on his record without considering that he was a teenager when he was arrested or that he is “gainfully employed at a large nonprofit, a father of two children … and volunteer in my community” today.

“There are a lot of assumptions of people with criminal records … and what that means about a person,” Williams said.

He argues that people can’t “contribute meaningfully to a community” without housing.

“Denying people housing is not necessarily keeping people safe,” Williams said. “It’s putting people already in dire straits in even more dire straits.”

As a landlord, Gray said the convictions she cares most about are sex offenses, violent crimes and recent burglaries. “If it’s been 10, 15 years, people can change,” she said.

Is Granite City ‘distorting’ the law?

Granite City relies on a 2002 Supreme Court opinion for its defense of crime-free housing in the litigation. The justices decided that a federal law from the “War on Drugs” era gives public housing authorities the discretion to evict federally assisted, low-income tenants if anyone in the home or guests who visited were arrested with drugs, whether or not those tenants knew about the drugs. They’re known as “one-strike” evictions.

Law professor Kathryn Ramsey thinks local governments are “distorting” the federal law the Supreme Court upheld to pass crime-free housing ordinances, which she argues are “significantly more harmful to tenants” than the one-strike policy has been, according to an article she wrote for the 2018 UCLA Law Review.

“The Court did not address any issues beyond congressional intent, such as the wisdom or effectiveness of the underlying policy, and it did not indicate that its holding would apply to any situation beyond the federal one-strike policy for public housing residents,” she wrote.

Former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor described the policy as “draconian” during oral arguments of the case in 2002. O’Connor retired in 2006.

“The position of the government in saying that any misuse by any guest, whether on or off the premises, will result in a forfeiture does seem to operate in a rather draconian fashion in some of the examples we’ve been given in the briefs. And one wonders why the government wants to take such an extreme position even though it lawfully could,” she said.

One measure of success for a crime-free housing program, according to the International Crime Free Association, is a drop in the number of police calls to rental properties. The BND asked for police call statistics in Granite City, but the police chief didn’t provide the information.

The number of letters the crime-free housing officer mailed did decrease from 94 in 2014 to 37 in 2018. It was back up to over 55 in 2019 before the end of the year, which is more than there had been in 2017 or 2018.

Gedge, of the Institute for Justice, said he would suggest municipalities control crime through criminal laws instead of rules for renters.

“The best way to address those crimes is to prosecute the wrongdoing and not make their friends and family homeless,” he said.

One mother brought up the effect an eviction would have on her children in her 2016 appeal.

“I have three children who attend elementary schools and this would be too devastating for them and our family as a whole,” she wrote to the city.

Her adult son was charged with dealing drugs near a park. She said he lived with his father, not with her. The outcome of her appeal wasn’t recorded in the city’s documents.

Werth says the decision to evict someone shouldn’t be taken lightly or made “on the basis of a mere accusation that has not been substantiated.”

“There’s both practical reasons to do that and reasons of justice and fairness,” she said. “People of color are much more likely to be accused of crime or have the police called on them.”

What’s it like to appeal when you’re facing eviction?

In the past five years, only 20% of the households facing eviction have tried to appeal at the municipal level like that mother.

Werth said few people might be exercising their right to an appeal because the letters about crime-free housing violations are coming from the police. By appealing, she said they would be “second-guessing the police.”

“For tenants and landlords, that is a very intimidating thing,” Werth said.

She suggests making code enforcement employees the ones to communicate with landlords and tenants about violations.

In her experience as a Granite City landlord, Gray said the crime-free housing officers have been reasonable. She thinks they would be willing to work with renters to find a solution other than eviction, especially if they didn’t know a crime was being committed, like a parent whose child’s friend brought drugs into their home.

Video: ‘We’re trying to protect our city,’ landlord says of crime-free housing

“It’s not something that is written in stone,” Gray said. “… You have the right to appeal it. When they send you those letters, it doesn’t necessarily mean this is what you have to do.”

In the past five years, the city’s hearing officer — an attorney based in another town — came to the same decision in appeals, that “the landlord must begin eviction proceedings,” at least 36 times. In six of those cases, it was a default decision because the renter didn’t show up for the hearing.

The hearing officer decided against eviction just seven times, according to documentation from appeals provided by Granite City in which a decision could be determined.

In 22 other cases, the documents were either completely redacted or there was no record of the decision.

At least 10 landlords appealed their tenant’s evictions or showed their support by writing to the city on the tenant’s behalf. One of those appeals was successful. Another six failed to convince the hearing officer. City documents didn’t include a decision for two others, while another document said the landlord could hold off on the eviction if the tenant moved out.

A landlord argued in an unsuccessful appeal from 2014 that the tenant was out of town when his daughter was caught with drugs at their home. She wouldn’t be allowed to come back because the tenant was going to change the locks, the landlord assured the city.

One renter was unsuccessful at the municipal level when she appealed in 2016, but when it went to court, a judge found “insufficient evidence of a lease violation after hearing evidence of underlying circumstances.”

Her son was arrested for fighting with someone down the street. He didn’t live with her but would visit. She had begged the city to let her stay.

“I do not have anywhere to stay or go at this very moment. … Pls (sic) don’t evict me,” she wrote in a letter requesting the appeal. “I have nowhere to go.”

Even though she was able to stay in her home, she had to agree that her son couldn’t come back to the house. About a year after his arrest, he was homeless, according to court filings, which recorded his change of address.

‘Are you going to deny them a place?’

Laurence Madden’s grandson had been banned from the apartment complex for his behavior two months before the arrest that triggered Madden’s eviction, according to a no-trespass order from police.

But his grandson was homeless, too, and his granddaughter Mandy Edwards said it would have been difficult for Madden to turn family away.

Madden adopted Edwards and his grandson as children, when their parents weren’t around to take care of them because of death or incarceration. Edwards said he wasn’t perfect; he could be manipulative, emotionally abusive and prejudiced. He was also fiercely protective of his family and would do anything for them, she said.

“If you saw your little brother or your cousin out there hungry on the streets — you know they’re messing up — but are you going to deny them food?” Edwards said. “When it’s raining and cold, are you going to deny them a place?”

In the five-year period the BND analyzed, 14% of renters faced eviction because of allegations against their guest alone, including Madden. And for one out of every three households facing eviction over a guest, the allegations didn’t result in a criminal conviction.

Madden was confident he couldn’t be evicted for a crime he didn’t commit, Edwards remembers.

He appealed his eviction at the municipal level and defended himself when it later went to court.

“He thought he was going to win this,” Edwards said. “He thought he was going to win the case. He’s like, ‘There’s no way.’”

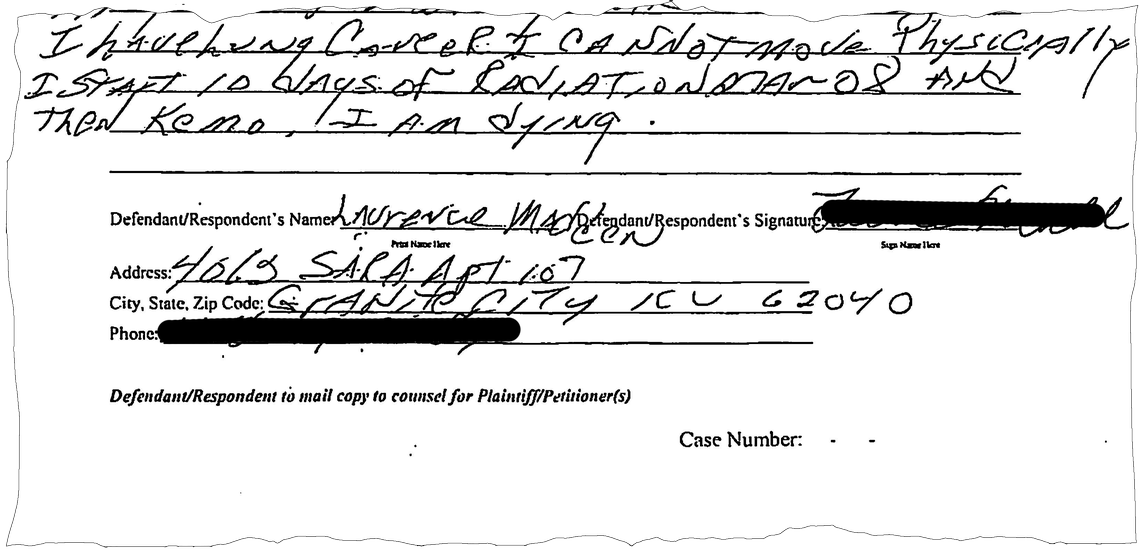

He explained that his grandson’s criminal charge — the one he was facing eviction over — had been dismissed and that he would be starting radiation and chemotherapy soon.

“I cannot move physically,” Madden said in a handwritten response to the eviction complaint in court. “ … I am dying.”

A “consent judgment” was entered in the landlord’s favor in his court case because, after fighting the eviction for more than three months, Madden finally agreed to leave his apartment.

No one in his family was able to take him in, and his health was deteriorating, according to his granddaughter. At the end of his life, Edwards said her grandfather felt like a burden.

He died in a hospital the day before he was supposed to be out of his apartment.