Originally published Nov. 13, 2023, by Belleville News-Democrat

CAHOKIA HEIGHTS — Yvette Lyles has twice been infected with a bacteria more common in developing countries that lack basic sanitation. But she hasn’t traveled.

Her son has had the same infection. So have over a dozen other people in Cahokia Heights, where residents have been exposed to sewage for decades.

If it doesn’t back up in a toilet, sink or bathtub, floodwater brings it inside. Sewage-contaminated water saturates crawl spaces and basements, inundates HVAC systems and soaks the floors and walls of living rooms, kitchens and bedrooms.

Some, like Lyles, are sure these living conditions made them sick.

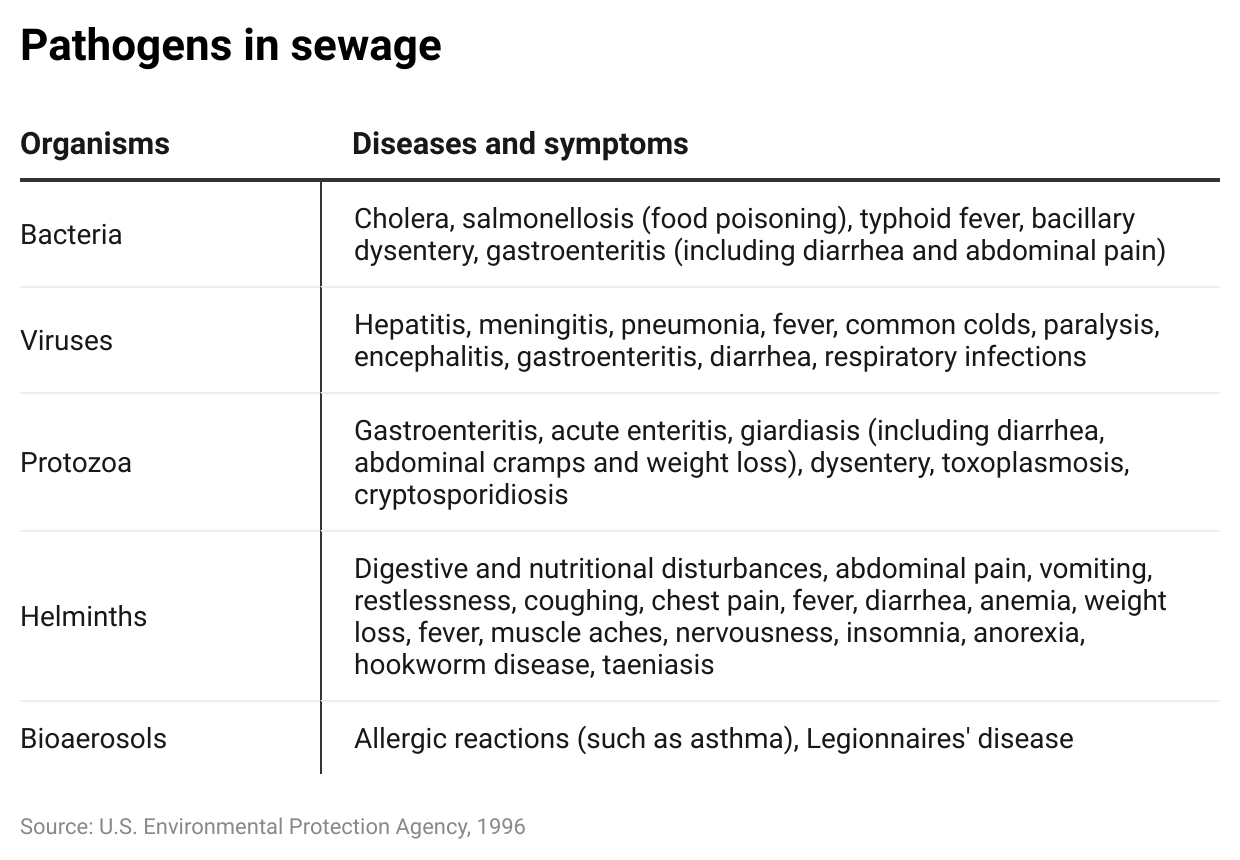

The water brings the threat of mold, as well as bacteria, parasites and viruses from human waste into homes.

But the local and state agencies responsible for handling serious public health threats like exposure to sewage have done little to nothing for residents over the years, a BND investigation found.

Neither the local health agency, the East Side Health District, nor the Illinois Department of Public Health, has investigated the possible health effects or fully informed residents of the risks, which are considered essential public health services.

“With the fact that we had raw sewage coming in our homes and in our neighborhood, the public health department should have been here right off the bat,” Lyles said.

The community’s problems are most pronounced where Lyles lives, in the northern area of the former city of Centreville, now part of Cahokia Heights. City equipment that should pump sewage away from homes is in disrepair. Heavy rain overwhelms the drainage system in the city and forces the sewers to overflow onto streets and residents’ properties. U.S. senators from Illinois described it as an urgent public health crisis three years ago.

The federal government has investigated public health agencies in another part of the country for failing to take action when sewage spilled into neighborhoods.

In Lowndes County, Alabama, the departments of Justice and Health and Human Services are now requiring health officials to find out who’s exposed to sewage and who’s sick from it, questions officials in Illinois haven’t begun to ask.

Health and Human Services hasn’t forced any action in Illinois, but this summer it started working in Cahokia Heights, asking residents about their health concerns. The federal agency hasn’t released any other information about its work.

Cahokia Heights residents who were tired of waiting have looked for their own answers in the absence of a public health response.

They’re partnering with universities to conduct a health study. It has found evidence that microscopic parasites and bacteria like the one that made Lyles sick are spreading in Cahokia Heights, possibly because of the sewer issues.

Universities look for bacteria, parasites

Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Colorado have been conducting a study in Cahokia Heights since 2022. The researchers shared preliminary findings with the community in August.

They discovered that over 40% of the 42 adults who volunteered to be tested last year, including Lyles, were infected with the bacteria Helicobacter pylori.

H. pylori infects the stomach after it’s ingested.

Experts believe people can pick it up if they touch an object or surface contaminated with feces. Even something that looks clean can still have germs on it. H. pylori can get into food if they don’t wash all the germs off their hands before cooking. Experts think it can spread from person to person by kissing. The bacteria can also infect people if it enters the water supply, often the case for those in under-resourced countries.

It is found less often in developed countries like the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The Illinois Department of Public Health downplayed the seriousness of H. pylori in response to BND questions about what the agency might do to assess the health effects of sewage exposure in Cahokia Heights in light of the study’s preliminary findings. Mike Claffey, the state agency’s spokesperson, said H. pylori is one of the most common chronic bacterial infections worldwide.

Claffey pointed to a study of data from a CDC survey in the U.S. between 1988 and 1991. The study estimated about half of U.S. adults over 60 had been exposed to H. pylori based on antibodies found in blood testing.

A study of an updated CDC survey between 1999 and 2000 found the numbers were declining in older age. Both estimated an average of around 30% of adults had been exposed to the bacteria.

The study in Cahokia Heights, on the other hand, analyzed stool samples showing how many people were actively infected.

Most people don’t experience symptoms from H. pylori.

One of the researchers in Cahokia Heights, Washington University Professor Theresa Gildner, said she and her colleagues hypothesize that healthy bacteria can help keep it in check. They think it can make people feel sick if they’re exposed to a lot of H. pylori or other pathogens in the environment because of something like sewage spills.

Lyles, 64, said she was so sick from the bacteria that she couldn’t eat or drink anything — even water — without stomach cramping, nausea and vomiting. She lost about 12 pounds the first time she had it and 15 pounds the second.

She saw a specialist in gastrointestinal diseases in Missouri to get a diagnosis, and treatment required two medications each time, making her experiences expensive as well as painful.

H. pylori can cause ulcers in severe infections. Left untreated, it can also increase the risk of gastric cancer, research on long-term infection has shown.

Lyles, who is a former nurse, advises neighbors to think about getting tested for the bacteria. She stood at a recent community town hall meeting to tell everyone. “H. pylori is a horrible thing to have in your system,” she said.

At least 180 households in the former Centreville have had sewage in their homes and over 280 have had flooding, a survey by residents’ legal team found in 2021.

Researchers returned to Cahokia Heights in August and October to increase their sample size.

Gildner said in an email to the BND almost 70 more people have participated, though not all of them provided stool samples for testing.

Researchers have also been collecting soil samples and recently started taking swabs from residents’ faucets as they try to find out where people are being exposed to bacteria and parasites.

Sewage can make people sick in other ways. It can carry viruses like hepatitis A, which infects the liver. Airborne particles from sewage can also cause allergic reactions such as asthma.

The dampness and mold in people’s homes contribute to breathing issues.

Lyles’ four children constantly had sinus infections and bronchitis growing up. She said they didn’t have those conditions before moving to Cahokia Heights from Pulaski County in southern Illinois.

The first of her six grandchildren also grew up in the home and developed asthma. But when her daughter and grandchild moved away to Belleville, Lyles said the asthma went away.

Lyles herself developed adult-onset asthma. Earlier this year, she damaged her vocal cords from coughing while trying to clean up after a flood. It required two surgeries.

Homes full of mold

Patricia Greenwood can hardly remember what it’s like not to cough all the time.

She returned home to Cahokia Heights from another doctor’s appointment in mid-August coughing behind a face mask, her voice hoarse and energy drained.

The 73-year-old has a long list of respiratory problems: Asthma. Sinusitis. COPD with emphysema and bronchitis, diseases usually caused by cigarettes. She never smoked and neither did her husband.

Their 18-year-old adopted son Arthur also has trouble breathing, but it’s been harder for doctors to figure out what’s wrong. Arthur has Down syndrome and struggles to explain what he’s feeling.

He places his hand on his chest and says “Breathe,” and his parents know that means he’s having difficulty.

“It’ll stop,” his mother said to calm him on this day. “It’s gonna stop.”

He thinks he needs to be in an ambulance every time he feels sick, she said. They’ve called an ambulance for him once before and many more times for his dad.

At 72, Lonnie Greenwood has had three strokes, two heart attacks and a gastric bleed in his small intestine. He needs about 24 pills a day to manage his health.

In the Greenwoods’ home, mold grows on the walls in what should have been Arthur’s bedroom. Instead of his bed and possessions, it holds the family’s storage now.

But other rooms they frequent also contain spots of mold: The newly renovated bathroom. The dining room, just a few feet from the living room where toys are spread out on the floor and a TV plays cartoons while Arthur eats dinner on the couch.

Like other families in Cahokia Heights, the Greenwoods struggle to get rid of the mold no matter what cleaning products they use because their home gets hit by floods repeatedly and stays damp even between rains.

Their crawl space is almost always full of dirty water. Usually, they don’t invite people inside because they say it smells like a sewer.

Two streets over, Sheila Gladney’s basement was also full of muddy-looking water in mid-August.

Gladney, 73, said she can’t go downstairs anymore because of her asthma and bronchitis. Sometimes, she can’t afford to pay a company to pump the water out either.

Gladney’s respiratory conditions have been so severe she said she used to go to a doctor weekly to check her lungs. One day when she was walking to catch a bus home from work, she collapsed on the sidewalk. She said she retired at 52 because of her breathing issues.

At least 20 households in Cahokia Heights have respiratory problems. That’s how many the American Lung Association heard from when it offered to provide dehumidifiers, air purifiers and specialized vacuum cleaners to address moisture and mold spores in their homes. An Environmental Protection Agency grant paid for it.

Patrick Hattaway, a field director at the American Lung Association, recalled what he saw when they conducted home assessments to look for asthma and COPD triggers.

“Whole rooms, their walls would be covered in mold,” he said.

Even people with healthy lungs can feel sick from mold. But Hattaway said people with asthma and COPD can have a hard time breathing or need medication because of their exposure.

The biggest issue in Cahokia Heights, he said, is that after a flood, water doesn’t always recede right away so materials like drywall, carpeting and filters in HVAC systems fill with moisture.

Sometimes, it takes days for the water to recede, residents say in lawsuits they filed over the deteriorating infrastructure.

The water can get so high during heavy rain that it looks like a lake in front of residents’ homes.

“When it rains, you don’t sleep around here, at least me and some neighbors don’t,” Lyles said. “… It comes so quick.”

Some have had to wade through waste-filled water to escape.

Gladney’s husband lost one of his legs to amputation after a wound on his foot got wet and infected while making his way to a rescue boat.

Like Lyles, the Gladneys and the Greenwoods are sure living in Cahokia Heights caused their health problems.

They say stomach, breathing and heart issues are common.

Lyles’ next-door neighbor Tiffany Prater had a heart attack at just 40 years old. A block away, Sharon Smith, 62, has asthma and bronchitis.

In another neighborhood, Cornelius Bennett, 72, watched a neighbor lose a lot of weight unexpectedly. He learned it was from H. pylori infection. Down the street, Walter Byrd, 65, has had heart problems in the past and now breathing issues.

Health officials fail to take action

The BND asked for interviews with East Side Health District and Illinois Department of Public Health officials to find out what they had done for Cahokia Heights residents. They declined interview requests but answered some of the BND’s emailed questions.

With about 62 employees, the East Side Health District serves roughly 55,000 people in Cahokia Heights, East St. Louis, Washington Park, Sauget, Brooklyn, Caseyville and Fairmont City.

It doesn’t have an epidemiologist to identify what illnesses might have come from the sewage in Cahokia Heights, according to longtime public health administrator Elizabeth Patton-Whiteside. She said an investigation like that would be done at the state level.

But the health district hasn’t asked for the state’s help, she said, because it hasn’t received any resident complaints of specific illnesses caused by the sewer problems.

Lyles rejected Patton-Whiteside’s explanation. Public health officials have known for years that residents were exposed to sewage, Lyles said. When residents learned about the H. pylori infections from the universities’ health study, they shared the information with the health district.

“How dare they ignore our issue,” Lyles said.

About a dozen residents from the hardest-hit neighborhoods said in interviews the East Side Health District has never asked them about their health. It has only come out to treat the sewage-contaminated water that pooled on the ground with larvicide to control mosquitoes.

The East Side Health District hasn’t helped educate residents about illnesses associated with sewage exposure or their symptoms, according to residents and examples of educational material the district provided to the BND or promoted on social media.

The provided educational material focused on mosquitoes and floods. Patton-Whiteside said her agency gave it to citizens who visited the resource center that opened in August 2022 after historic rainfall caused severe flash flooding across the region. A post on the district’s Facebook page from around the same time was the only example the BND could find of the agency explaining how residents could protect themselves when cleaning sewage out of their homes.

In Alabama, which is facing similar issues, the federal government required health agencies to deliver detailed information about sewage door-to-door when possible, as well as through radio and print ads, flyers and mailers. They also had to notify medical providers of the sewage issues in Lowndes County.

They advised Alabama physicians to ask about residents’ exposure to sewage, especially if they came to the doctor’s office with gastrointestinal symptoms like cramps, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, to help diagnose infections from viruses, bacteria and parasites, including hookworm. An independent study found hookworm is spreading in Lowndes County.

“As far as what the Biden administration is doing in Alabama, I applaud their efforts,” Patton-Whiteside stated. “… To date our Environmental Health Services does not have enough manpower or resources to do the same. This would have to be undertaken by IDPH.”

Alabama health officials are also getting help from the CDC to investigate the prevalence of infectious diseases in Lowndes County and assess residents’ risk. Any health official can request the CDC’s help responding to a local public health issue, according to its website.

State and local health officials in Illinois haven’t taken action on the sewage issues in Cahokia Heights even as extensive media coverage over the last three years has detailed residents’ chronic exposure.

In response to BND questions about the Illinois Department of Public Health’s role in Cahokia Heights, Claffey, the agency’s spokesperson, said state epidemiologists didn’t see any increases in gastrointestinal diseases in 2020 through the disease surveillance system. Doctors are required to report certain infectious diseases to the health department for further investigation. He noted H. pylori infection isn’t one of the illnesses that requires reporting and investigation.

The East Side Health District didn’t respond to a BND request for comment about the H. pylori infections the health study discovered in Cahokia Heights.

Residents like Lyles think public health agencies haven’t done enough for them.

“I’m inclined to believe that everybody wants to drop the ball,” Lyles said. “… Everything is a process but making us live like this was a process, too, and no one seems to care about it.”

“To be honest with you, I’m angry,” she added.

Residents have wanted to learn more about how their living conditions might have affected their health for years. They criticized city officials for not seeking funding for health testing, among other aid they wanted, as the local leaders applied for a large amount of federal money to address infrastructure problems in 2021. Their efforts followed the consolidation of Centreville, Alorton and Cahokia into Cahokia Heights.

Cahokia Heights Mayor Curtis McCall Sr. didn’t respond to a request for comment for this article. He was the Centreville Township supervisor and served on the board of health for the East Side Health District before becoming mayor.

Public health officials have said the city is taking care of infrastructure problems in Cahokia Heights, with oversight from environmental protection agencies. But while the EPA enforces rules about how public sewage systems should operate, it doesn’t determine health effects when a system malfunctions.

One of the same federal agencies that investigated Alabama is now asking questions in Cahokia Heights. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recently started working in Cahokia Heights along with the EPA, federal officials said in emails to the BND.

This summer, it organized a meeting with residents to ask about their health concerns, according to Lyles, who was present. It also met with environmental officials about how the EPA’s enforcement actions protect public health, an EPA spokesperson said.

The EPA has ordered the city to repair the sewer system and water providers to monitor drinking water.

Health and Human Services declined to provide more details about what it’s doing in Cahokia Heights and why it’s involved now. Officials wouldn’t agree to an interview.

Its investigation with the Justice Department in Lowndes County was the first of its kind because it considered whether a government agency discriminated against Black residents by not protecting them from hazards in the environment that could make them sick.

Lowndes County is a predominantly Black, low-income community much like the former city of Centreville, where over 90% of the residents are Black and three in 10 live below the poverty line.

The Justice Department said it had no comment about Cahokia Heights.

Environmental activist Catherine Coleman Flowers, who led the effort for a public health response in Alabama, said she hopes other health officials don’t wait until the Justice Department is knocking on their door to take action.

She visited Cahokia Heights four years ago and said she remembers toilet paper littering residential streets, shockingly close to a big city. It’s less than 10 miles from St. Louis.

Drinking water under scrutiny

Lyles believes the tap water in her home is the reason she’s been infected with H. pylori twice.

After the first time, she stopped drinking or cooking with it, and after the second, she stopped using it to brush her teeth. Her family tries to avoid bathing in the water by going to a YMCA in another town most mornings to take showers there.

Other residents have also stopped drinking from the tap, keeping stacks of bottled water on hand. They say they don’t trust the water in their homes because at times it’s brown, foul-smelling, cloudy or it has visible particles in it.

Private water company Illinois American Water serves the old Centreville area. In an interview and in community newsletters, company officials said the water is safe to drink and offered explanations for residents’ concerns.

The company said discolored water, for example, can be the result of main breaks, flushing, fire departments’ use of hydrants or water contacting bare iron when the coating inside pipes wears away.

In 2021 following resident complaints, the EPA said it had concerns about the potential for sewage to contaminate the water.

Because sewage was on the ground near buried pipes, it could enter the drinking water system through cracks that might exist if those pipes were to lose pressure, according to the federal agency. At the time, Illinois American Water wasn’t collecting water samples in those places to test for possible contamination.

It mostly chose businesses because they’re accessible to collect water when schedules allow, according to Rachel Bretz, the company’s director of water quality.

The EPA asked Illinois American Water to add collection sites in the former Centreville where sewage spills. For two years, the company was required to collect a water sample for testing within 24 hours of each spill. It also had to repair some of its infrastructure.

Water providers look for the presence of coliforms, a group of bacteria that includes those from feces and others that are harmless. Finding them requires more testing to determine if harmful ones, like E. coli, are present.

Illinois American Water hasn’t found E. coli in the former Centreville, according to a company spokesperson and a BND review of water test results from the past decade.

The EPA halted the increased monitoring in July after the infrastructure upgrades were completed. Illinois American Water said it will continue using the new Centreville locations for regular monthly testing.

Residents’ lawyers Nicole Nelson and Kalila Jackson said they sent the EPA the preliminary findings from the health study before the agency decided to stop increased water monitoring. In a statement, the EPA said it welcomes the input from the scientific community.

“We look forward to reviewing all further work on these important questions,” the agency stated.

Community still waiting

Lyles has reminders everywhere that the contents of sewer pipes have been invading her family’s home since 1997: the pungent smell when she opens the front door, the waterlines on the baseboards and the legs of her furniture, the slanted floors and the cracked walls. She placed a floral decoration on top of one large crack that formed over her bedroom closet to hide it from constant view.

Her neighborhood floods three or four times a year, damaging properties and spreading sewage around.

Some have wondered if they’ll live to see it end or if their houses will remain standing until then.

“It can only take so many hits and then that’s it and a home will just fall apart. Imagine people’s body the same way,” Lyles said. “Your body can only take so many illness before you drop dead.”

After her son got sick from H. pylori, Lyles said they talked about the hazards in their home. She thought of the neighbors who she knew died of GI cancers and cardiac problems with no family histories of those issues.

“Could it be our environment that did this to them?” she recalled thinking. “I am inclined to believe yes.”

Neighbors have moved away over the years, some abandoning their old homes. But many others don’t want to leave. A group of residents is trying to force local government agencies to fix the problems and compensate them for property damage through federal lawsuits so they can stay.

They like the neighborhood and know all their neighbors. And they question how much they’d get for their homes now. They look at the housing market and don’t think they could afford similarly sized properties in another location.

So they wait and hope.

And when it rains, they watch for rising water and worry.