Originally published Jan. 2, 2022, by Belleville News-Democrat

It was common knowledge in the nursing home business, but perhaps not to the families trusting those facilities with a loved one’s care.

For years before the coronavirus pandemic, the industry and government regulators knew that nursing home workers repeatedly made errors that could potentially spread germs and cause infections among their patients.

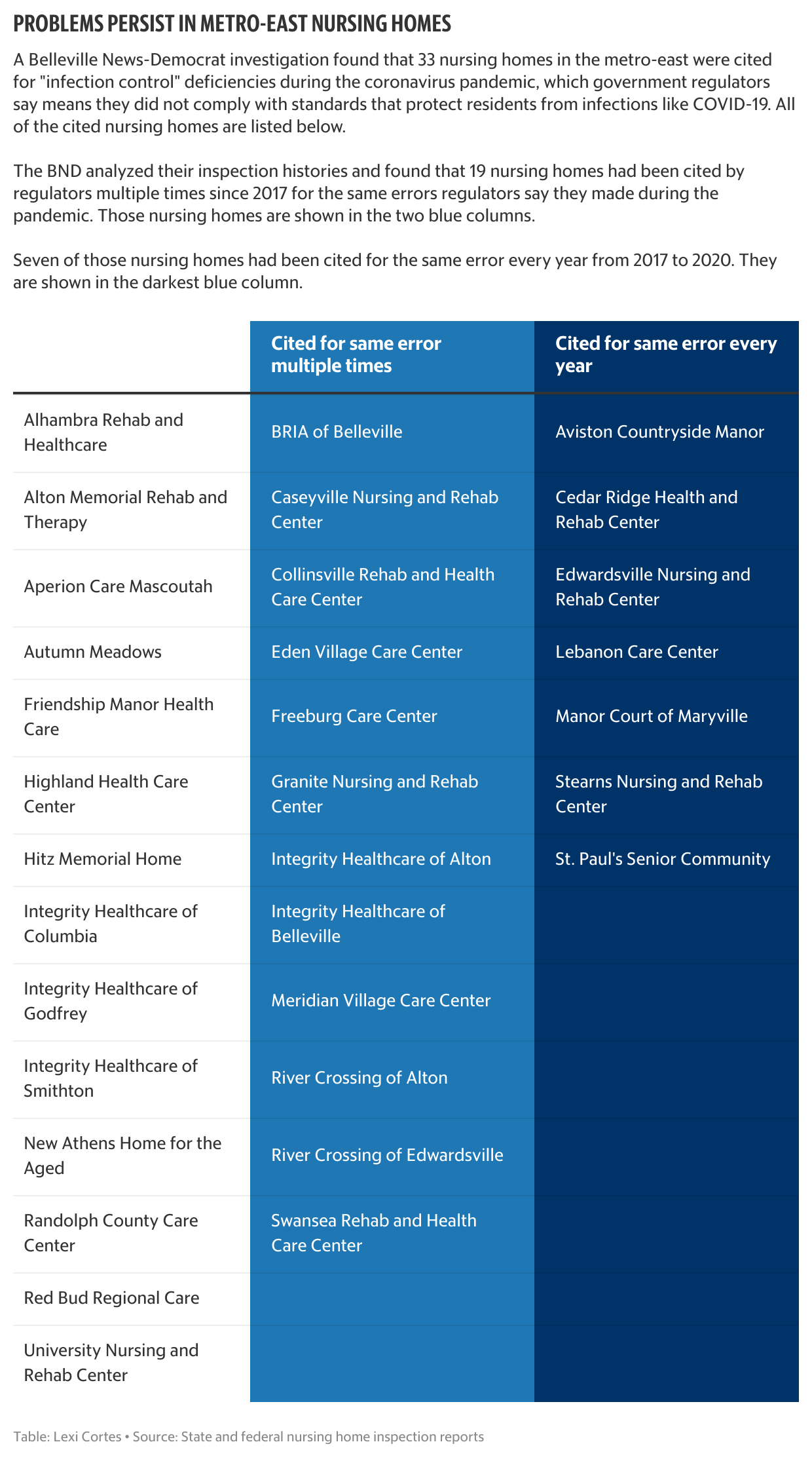

In the metro-east, 40% of the nursing homes had been cited multiple times since 2017 for the same errors during inspections, and they continued to make those mistakes during the pandemic, a BND investigation found.

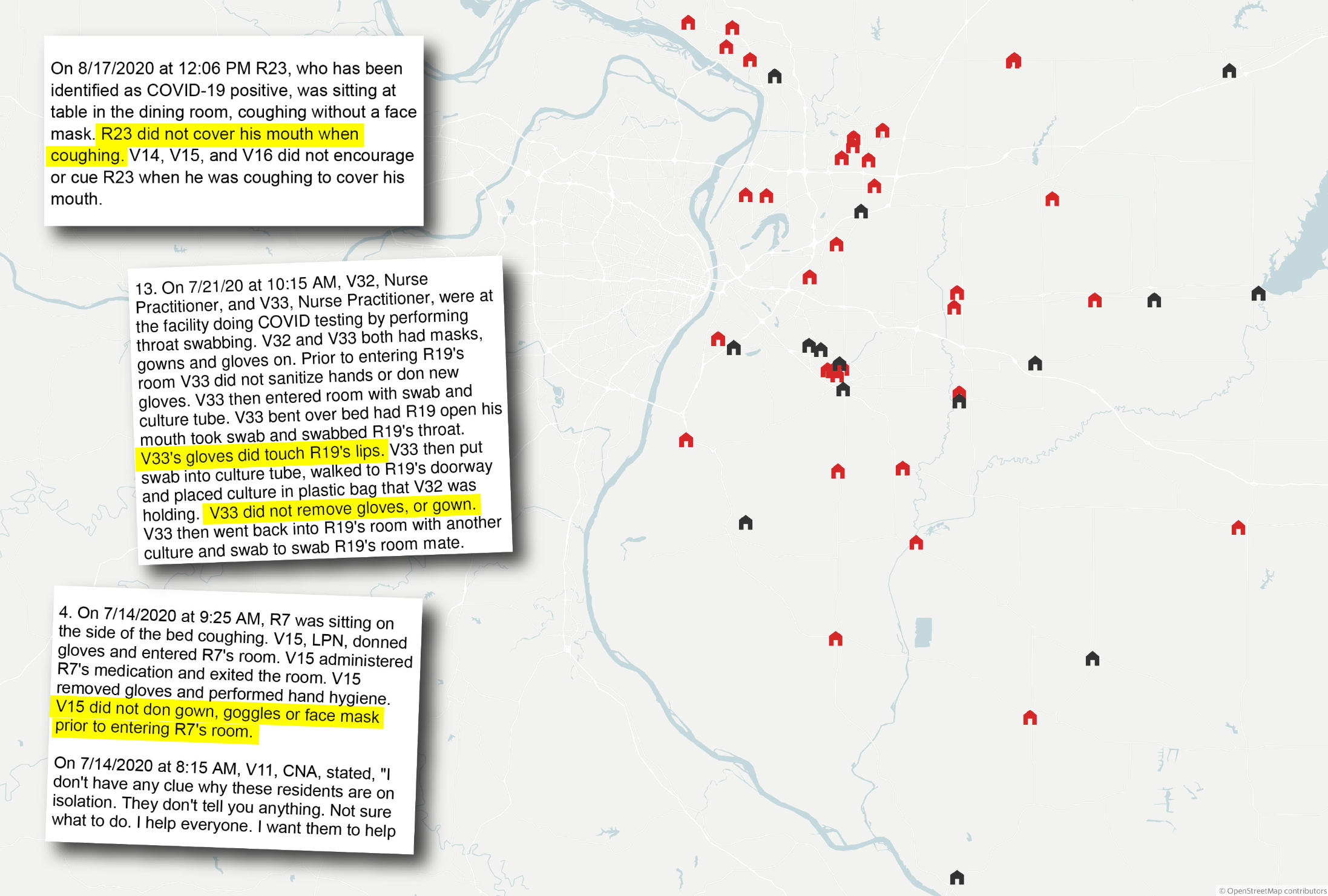

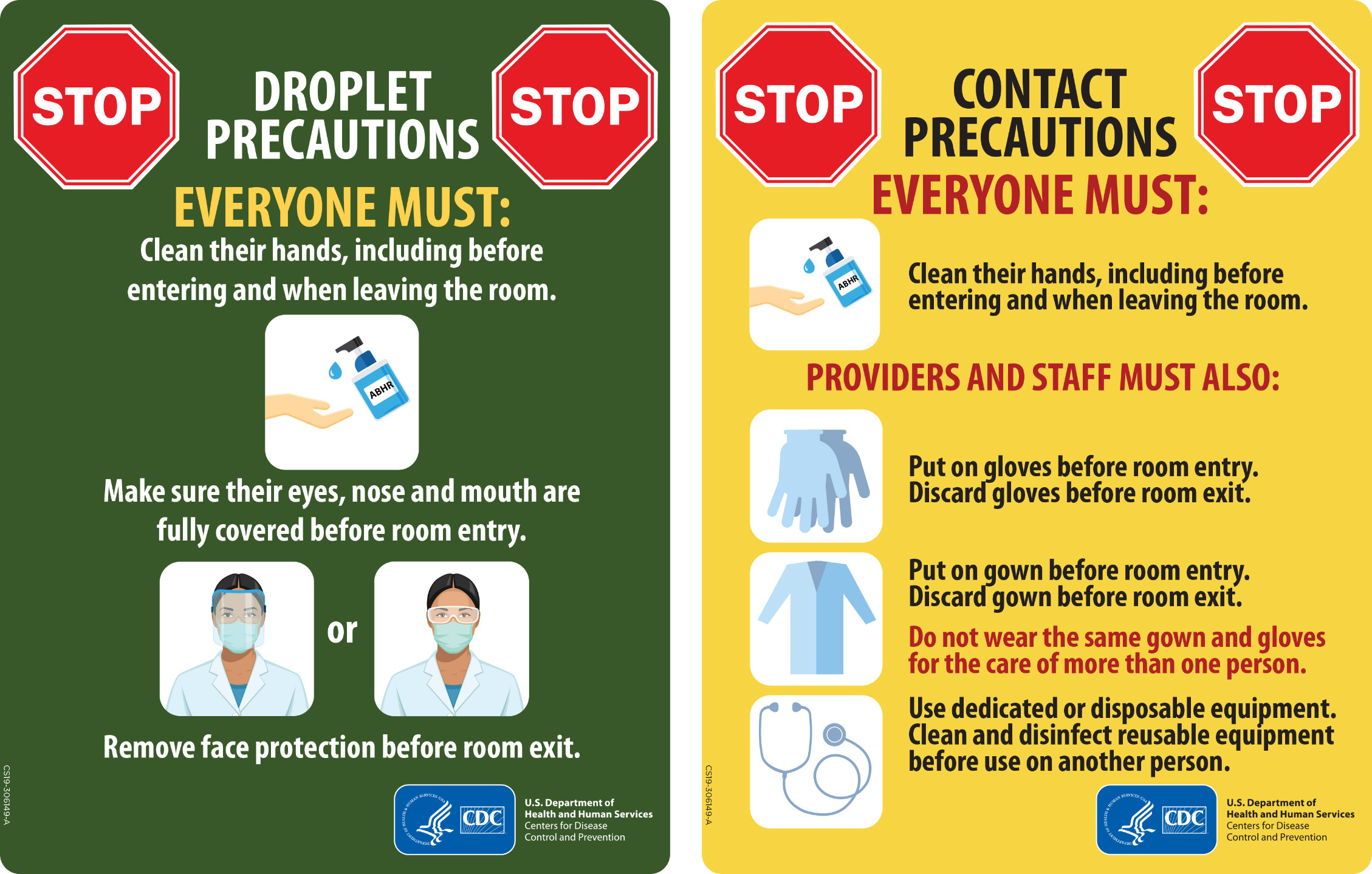

Local workers struggled with what regulators describe as the fundamentals of “infection prevention and control” requirements. They didn’t always clean their hands, put on personal protective equipment like gloves and face masks or change out of gear that could have been contaminated.

And the mistakes persisted despite rules dictating how workers should act to prevent infections and state inspections that were supposed to hold them accountable for failure.

“Don’t worry about putting that on (PPE). No one else does,” a local nursing home resident with a contagious infection told an inspector entering her room in late January 2020. Their conversation was less than two months before Illinois first detected the coronavirus in a nursing home.

“The nurse was just in here she didn’t put it on and didn’t wash her hands,” the resident added. “They never put those on unless they are scared someone’s going to be looking at them. … They are supposed to though.”

It’s difficult for inspectors to say how many of the more than 4,700 COVID-19 diagnoses in metro-east nursing homes might have been caused by violations of infection standards. Inspectors base their reports on what they observe during an inspection over one or more days, what they hear from residents or employees and what they find documented in a nursing home’s records.

“It can happen to anybody, but if you’re breaking infection control protocols, you’re inviting an outbreak,” Chris Sutton, the region’s former long-term care ombudsman, said in an interview. “… If infection control protocols aren’t followed, it’s going to make it worse.”

In its investigation of nursing homes and their government oversight, the Belleville News-Democrat analyzed 114 inspection reports covering nearly five years, including the pandemic, and other data to identify the trends that have endured in the metro-east.

The BND investigation found:

- Inspectors visited all 48 of the region’s nursing homes for an inspection during the pandemic.

- 69% of nursing homes— 33 out of 48 — were cited for “infection control deficiencies,” an industry term that means they didn’t comply with hygiene and safety rules workers are expected to follow to protect patients from disease.

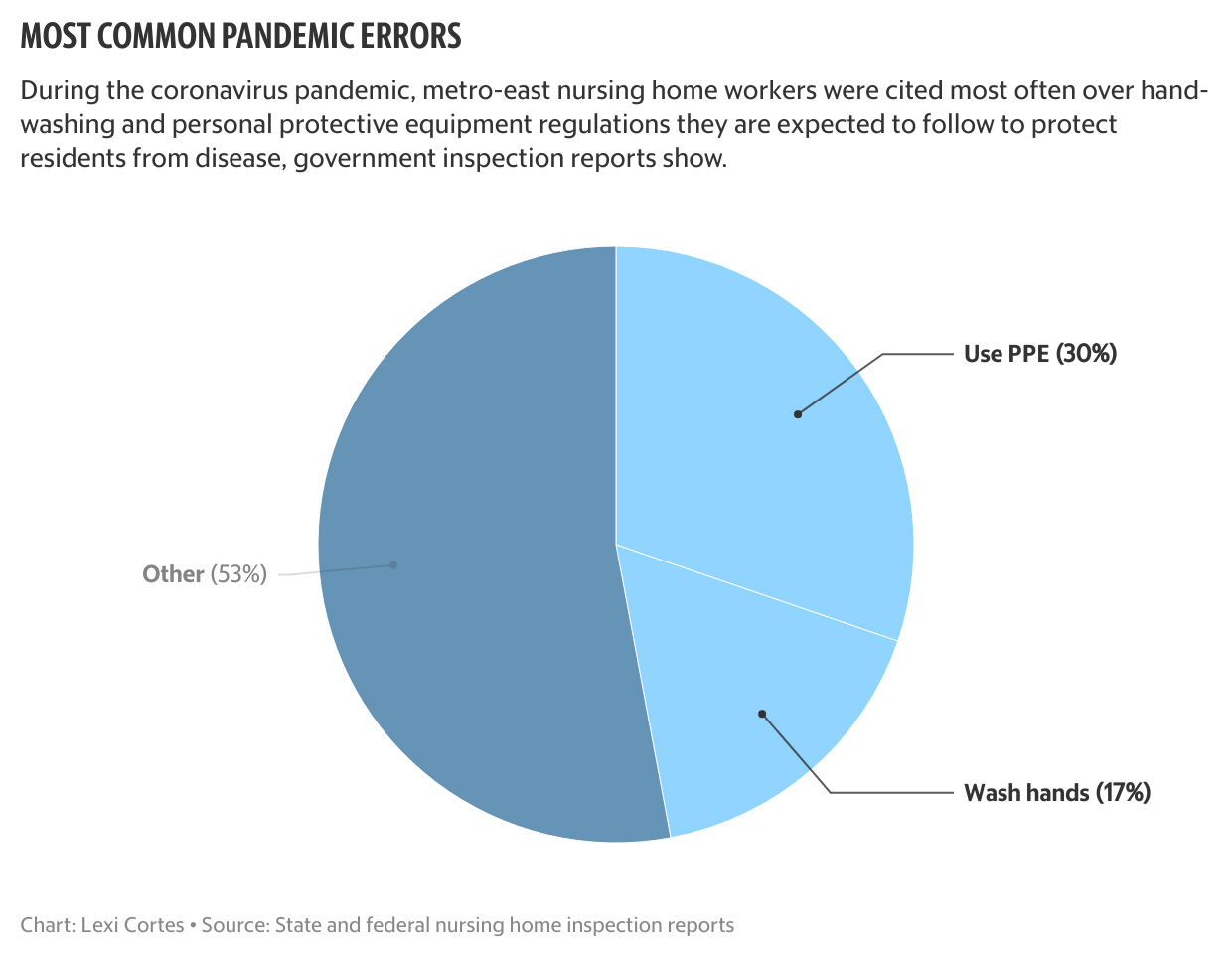

- The circumstances included leaders allowing residents with COVID-19 to mingle with residents who weren’t sick, which was considered the most serious error, and employees failing to clean their hands or use PPE, which were the most common errors.

- Inspectors said errors uncovered during three nursing homes’ inspections resulted in 81 resident infections and eight deaths from COVID-19.

- The three nursing homes — Stearns Nursing and Rehab Center in Granite City, Integrity Healthcare of Smithton, and Friendship Manor Health Care in Nashville — received the most serious citation available to regulators. Inspectors determined residents’ health or safety was in “immediate jeopardy” based on how severely they believed residents were harmed or could potentially have been harmed by the errors.

- Integrity Smithton and Friendship Manor sought to appeal their citations in 2021, according to nursing home and state representatives. Stearns said through a lawyer it was evaluating its appeal options after receiving the citation. It’s not clear whether Stearns eventually filed an appeal. The appeal process isn’t publicly announced until there is a decision.

- 47% of all the errors in the region were related to PPE or hand-washing, expectations that a number of metro-east nursing homes had already been struggling to meet before the pandemic.

- 40% of nursing homes — 19 out of 48 — were cited over hand-washing or PPE use between two and four times in the years leading up to the pandemic.

- 15% of nursing homes — seven out of 48 — were cited over hand-washing or PPE use every year from 2017 to 2020.

- The chaos of a pandemic, with evolving guidance for how to fight a new virus, helps explain some of the errors since 2020. At 19 of the 33 cited nursing homes, leaders at times didn’t give clear or correct information to employees about the required steps to prevent the coronavirus from spreading, inspectors found.

- 21% of the nursing homes cited with infection control deficiencies — seven out of 33 — were also cited during the pandemic for staffing levels so low that inspectors said residents weren’t getting the basic care they needed.

- Nearly all of the nursing homes — 43 out of 48 — were short-handed at some point in the pandemic, according to information they reported to the federal government on a weekly basis about shortages of nurses, aides and other employees.

Throughout the pandemic, the BND gathered perspectives on nursing home issues and possible solutions from more than three dozen people, including area nursing home administrators, workers and families; local, state and national resident advocates; and state officials, lawmakers and trade group leaders through interviews, written statements, news conferences, virtual town halls and legislative hearings.

People representing the different sides of the business — patients and providers — agree that frequent staff turnover and widespread worker shortages contribute to the repeated errors.

“A lot of times they do skip corners on infection control because they’re trying to cover an entire hall by themselves, which is impossible,” said Tracie Ramel-Smith, the metro-east’s new regional ombudsman.

Errors also persist because of lax enforcement of infection standards, limited supervision of workers and, often, a revolving door of new administrators, according to local and national resident advocates.

Using a questionnaire, the BND asked for comment from administrators at all 33 nursing homes that inspectors cited for breaking infection control rules during the pandemic. Two administrators filled out the questionnaire. Two more nursing homes responded through a corporate spokesperson and an attorney.

These officials, as well as trade group leaders, say nursing homes and their workers did the best they could in the extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic.

“This is a very trying time for all,” Michelle Cato, administrator of Randolph County Care Center, said in response to the BND’s questionnaire. “Staff members are going above and beyond to ensure the safety of our residents and family members. I think everyone in the health care profession is doing an outstanding job with what we have to work with.”

Virus infects thousands in Illinois nursing homes

Experts agree that infection standards are crucial to protecting nursing home residents from getting sick, which is important because they have a greater risk of severe or fatal illness due to their age and health problems.

But even nursing homes that weren’t cited for breaking those rules had sick residents. The highly contagious novel coronavirus was spreading while experts studied it to provide guidance and health care professionals sought the supplies necessary to fight it.

The coronavirus had infected 4,725 metro-east nursing home residents and workers by mid-December 2021, killing 574 of them, according to statistics nursing homes are required to report.

Across the state, 66,410 Illinoisans who lived and worked in nursing homes were infected and 7,442 died from COVID-19. They made up more than a quarter of the COVID-19 deaths statewide as of Dec. 12, but the proportion had been even higher in the early days of the pandemic, long before vaccines became available and slowed transmission in nursing homes.

Joyce White, 60, was one of the metro-east nursing home residents whose death the state investigated, according to details from an inspection report verified by her family.

Her daughter Elyse Coil remembers White’s complaints during the pandemic were about waiting for workers at Friendship Manor Health Care in Washington County to answer a call light at times.

Coil knew they were probably dealing with shortages. White thought they might not want to come into her room because of all the PPE required.

“It could be an hour before they came to see what she needed,” Coil said. “… Sometimes she felt like they didn’t want to mess with her, maybe because they had to gown up. She just kind of felt like she was a burden.”

Friendship Manor had shortages of nurses, aides and other employees during its coronavirus outbreak, according to information it submitted to the federal government. The facility’s leadership said they struggled to find help when they advertised open positions and asked for workers from Illinois’ health care volunteer network and medical temp agencies.

Now, in the aftermath of COVID-19’s devastation, more Illinois lawmakers and state officials are paying attention to nursing homes and working with new urgency to fix systemic issues — infection-control errors and staffing shortages — that had been allowed to persist for years.

“It’s past due,” said Becky Dragoo, a new state official overseeing nursing home enforcement. “It’s heartbreaking that the attention is as a result of so much serious injury and harm and death to residents and pain and grief to their families.

“It really is heartbreaking. But we are moving in a positive direction. And I think the changes that we’re making are thoughtful and they’re lasting, and I believe that they will make the difference in terms of quality of care and quality of life.”

Turnover, shortages a long-standing challenge

Resident advocates, workers and managers say worker shortages make it more difficult to ensure there are enough people to take care of residents and follow time-consuming procedures that keep them safe. And constant turnover makes it more difficult to ensure new hires have the training they need.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office, a watchdog agency that analyzed nationwide trends in nursing homes’ infection control deficiencies, heard the same responses from researchers and representatives from industry and resident groups.

A local nurse who spoke to the BND said her experience in three metro-east nursing homes was that workers regularly cut corners because “there’s never enough staff.”

“They do what they gotta do to get through the day,” the nurse said. She asked the BND not to use her name out of fear of retribution because she continues working in long-term care.

Industry representatives say the public funding they get in Illinois has been too low to offer wages that attract or retain employees, which led to shortages and turnover. State officials say they’ve given the industry more money three times in recent years — $160 million since 2014 — to try to help them increase staffing without across-the-board results.

Richard Mollot, of the national research and advocacy group Long Term Care Community Coalition, is skeptical of anyone in the business who has said finances were dire. He says the proportion of for-profit facilities is growing. In the metro-east, most nursing homes are run by for-profit companies — 39 out of 48.

“Clearly it’s a money-making endeavor,” he said.

Mollot’s group studies public data to help make its case that each nursing home should employ enough people to provide quality care to residents. Illinois consistently ranks low in terms of staffing, according to the Long Term Care Community Coalition’s analyses.

Mark Cooper, an Illinois nursing home resident, testified at a recent state legislative hearing that the quality of his facility was “dramatically worse than it used to be” as staffing decreased over the last year through the pandemic and under new ownership. He did not identify the nursing home where he’s receiving care.

Cooper thinks local administrators’ hands are tied by the owners, who make decisions about workforce cuts and who control the cash flow. “I think they’re hamstrung by what amount of money, frankly, they are allowed to work with,” he said in his testimony.

AARP Illinois advocates and state lawmakers have expressed concerns in the hearings that some nursing home owners have been putting money toward their own profits instead of in their staff.

Illinois is considering another funding increase but with accountability measures that require nursing homes to show their staffing levels improved.

Nursing home with no citations had high staffing levels

Clinton Manor Living Center in New Baden is one of the few metro-east nursing homes that had no citations throughout the pandemic, for infection-control errors or any other problem.

It faced all the same challenges COVID-19 created as other nursing homes. But what leaders there said made the biggest difference for them was their staffing levels, which have been among the highest in the region both before and during the pandemic.

Video: How one southwestern Illinois nursing home survived COVID-19

Darla Loomis, Clinton Manor’s director of nursing, said one secret to their success with hiring and retention is having opportunities for advancement.

Kitchen, laundry and housekeeping employees can go through Clinton Manor’s certification program to become certified nursing assistants. They can also get help from Clinton Manor’s board of directors if they want to go to school to become nurses.

“That’s really the only way to get them in,” Loomis said. “A lot of times when people leave and go try something, they’ll be back.”

Industry representatives and state officials are now proposing career ladders as a key solution to staffing troubles in nursing home reform hearings.

‘Need to do something a little bit different’

Local resident advocates Chris Sutton and Tracie Ramel-Smith said turnover at the management level is another issue for nursing homes that could be contributing to persistent infection-control errors. Sutton spoke to the BND before his death in August 2021. Ramel-Smith is his successor as regional ombudsman.

They say new managers might not know about a problem the staff has had with hand-washing or PPE in the past, so they don’t address it.

A majority of the metro-east’s nursing homes — 77% or 37 out of 48 — have experienced administrative turnover between 2017 and 2020, according to state questionnaires they fill out annually.

Fifteen of the 19 facilities with persistent errors that continued into the pandemic had administrators come and go over the four-year period.

“In some of our buildings, it’s constant administrators, DONs (directors of nursing). You never see the same people,” Ramel-Smith said.

Becky Dragoo, who is now overseeing the enforcement process at the Illinois Department of Public Health, said the state is interested in taking “more of a proactive approach” with persistent errors by tracking the trends in nursing home deficiencies and bringing that information to administrators.

“If we see, ‘Hey, this is a facility that time after time, we’re seeing infection control’…we want to ensure that we’re having a dialogue with that facility,” she said.

“I think that’s a new approach to what has occurred in long-term care. …We need to do something a little bit different,” Dragoo added.

Few nursing homes fined over infection control before COVID

Sutton and Mollot said in interviews that they have long known nursing homes don’t always comply with infection standards.

Sutton was familiar with the metro-east’s trends from his time with the region’s ombudsman program, helping resolve nursing home resident complaints in St. Clair, Madison, Clinton, Monroe, Randolph, Bond and Washington counties for five years.

Mollot knew the same trends were happening nationally from his experience advocating for residents through the Long Term Care Community Coalition for close to 20 years.

They say the punishment for infection control deficiencies isn’t working as a deterrent because it isn’t harsh enough. Usually, the state makes nursing homes give their staff refresher training. Fines are rare.

“In essence what that tells the industry is that ‘You have been found to have substandard care or practices, but we’re still gonna pay you, and we’re not going to penalize you,’” Mollot said of the public funding nursing homes receive, particularly from Medicaid.

“And of course that sends a message to an increasingly for-profit industry that that’s OK, that this level of poor care, substandard care and practice is fine.”

Dragoo, of the Illinois Department of Public Health, says state and federal rules restrict the penalties inspectors can seek. The threshold for fines is typically whether or not a nursing home’s error harmed any residents or was likely to seriously injure them.

In the years before 2020, metro-east nursing homes were often cited during daily tasks like changing an adult diaper or wound dressing, when workers should clean their hands and replace their gloves multiple times.

Fines became more prevalent during the pandemic because an infection became a greater threat to nursing home residents.

The BND could locate only eight local nursing homes that were fined for infection control deficiencies from 2017 to 2019 in a federal database. It increased to 31 facilities in 2020 and 2021.

Nursing homes can appeal citations and fines. If they waive the appeal, fines are reduced by 35%.

A northern Illinois lawmaker recently asked about possible reforms to fines during a legislative hearing, but it didn’t lead to public discussion about specific changes legislators might want to make.

“Money talks,” said State Rep. Terra Costa Howard, a Democrat representing one of the collar counties of Chicago. “And fines do mean something when there’s a lot of teeth to them.”

What is public health’s proposed reform?

Dragoo is a new Illinois Department of Public Health deputy director, in charge of its office of health care regulation. She said she came into the job in February 2021 with “the hope and the expectation” that she could lead the office through reforms.

She has experience as an operating room nurse, and she previously worked for the state health department on a team that reviews inspectors’ findings and imposes penalties for nursing homes. Dragoo also worked for the department on aging in a program that brings services to seniors’ homes as an alternative to nursing home care.

After returning to the Illinois Department of Public Health, Dragoo said one of the reforms her office started working on was ensuring nursing homes have a professional on staff known as an infection preventionist.

The person in that role would write and update a nursing home’s infection control policies and provide ongoing staff training, as well as daily oversight to make sure workers are following the rules.

Sutton, the former regional ombudsman, said nursing homes with persistent infection-control errors might not have had enough supervision in the past.

“It’s part of their training, but it starts breaking down because one, it’s a pain in the butt, and I know that, but it keeps people alive, so you have to follow it. But a lot of it is because there’s not enough supervision,” Sutton said.

As part of their job, ombudsmen go to nursing homes to check in with residents about their care. Ramel-Smith, the new regional ombudsman, said they rarely see supervisors walking the halls when they visit.

Regulators have been asking nursing homes to hire infection preventionists since a 2016 federal rule change made the position mandatory on at least a part-time basis starting in 2019. But it didn’t happen in many nursing homes until the pandemic, according to Dragoo.

The industry has said in response that regulators haven’t provided clear requirements for the position.

As of December, the changes around infection preventionists and new funding for nursing homes haven’t taken effect, but lawmakers are expected to return to the reforms in the spring.

“Now we know just how bad it can be, and we know that variants and new viruses exist,” said Andy Allison, of the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services, at a recent legislative hearing. He helped write the department’s funding reform proposal.

“Our children, our parents, our grandparents have been taught this in a way that none of us wish we would have had to have learned. … The urgency here is to protect from what we now know is very possible.”